Digital Twin Technology – why it is so important

- 25 December 2020

- Posted by: Future Energy

- Category: Energy

Virtual Reality(VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) can be applied to “Digital Twins” of process facilities. Both VR and AR are becoming increasingly popular in many industrial sectors but the uptake in oil and gas has, in comparison, been very modest.

The main applications to date have been concerned with training but there is a far broader range of opportunities that could be applied in the future. The real strength of these technologies is their capability to disseminate more meaningful information to the user through an immersive experience. Coupled with artificial intelligence (AI), they can enable a skilled intervention when an expert is otherwise unavailable.

Example work flows in remote oil and gas operations where VR and AR could make a real difference include:

Reservoir Monitoring

- Enhanced recovery monitoring

- Water flood monitoring

- GOW interface tracking

- Draw down test monitoring in wells

- Connectivity and fault leakage testing

Operations

- Process and equipment monitoring, including Preventative Maintenance

- Analytics visualisation – equipment and process

- Turn around planning and implementation in operating units offshore and refineries and petrochemical plants

Maintenance

- Planning and walkthroughs

- Real-time impact assessment – hot work – IoT integration

- Support for risk assessment

- Work & personnel tracking/monitoring

- Training

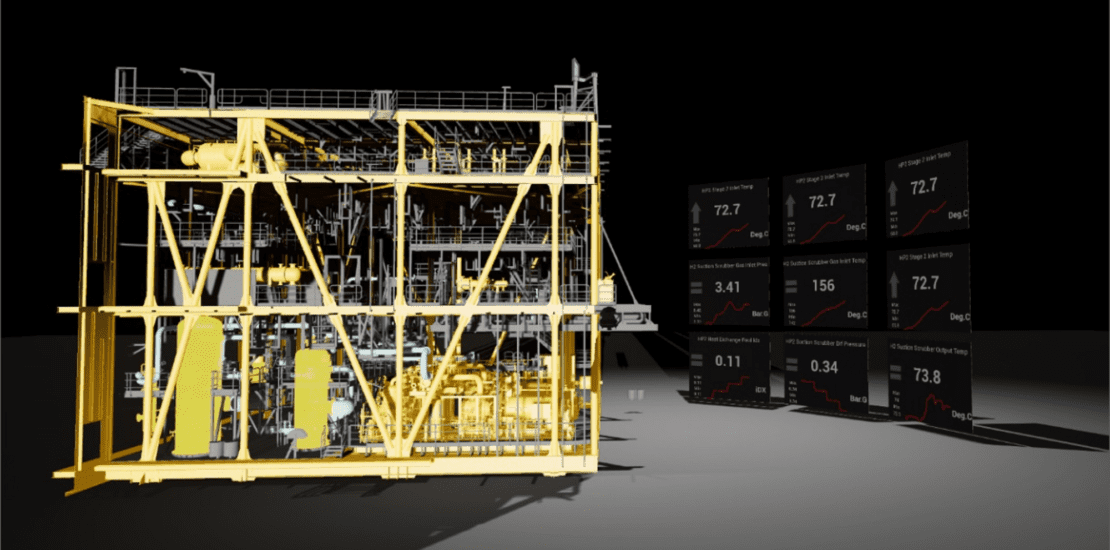

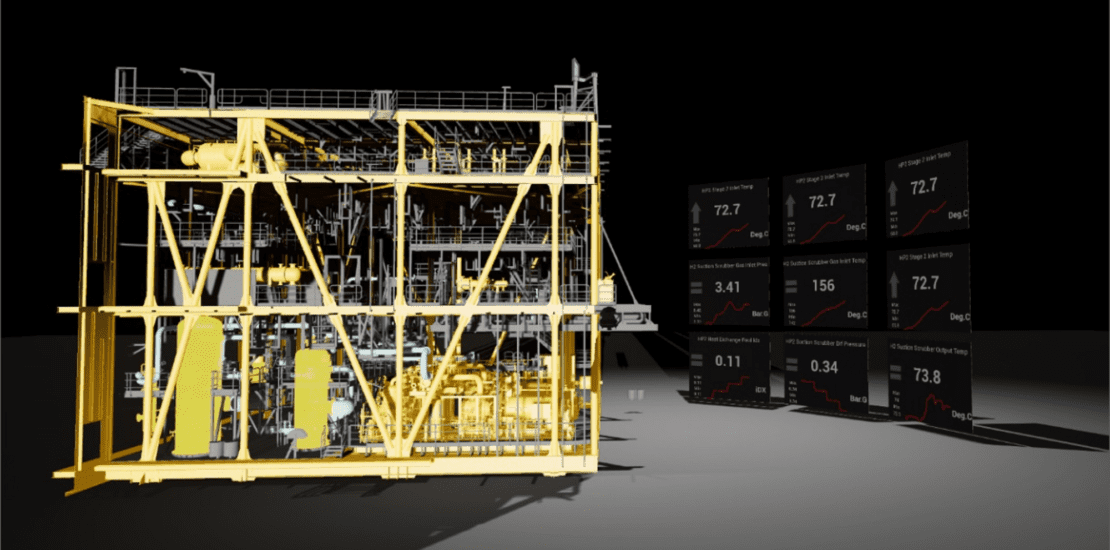

Figure 1 – below shows a Digital Twin of a typical gas processing facility that may be viewed on a conventional video screen in 2D or navigated in 3D using VR technology. Animating the Digital Twin technology with live plant information gives the user a true sense of “being there”.

This brings enormous value to operators by providing plant simulation, increased safety by reducing the number of personnel working in a hazardous environment and efficiency gains by enabling experts to diagnose performance issues without having to attend the plant. Both the 2D drawings and 3D Digital Twins can be readily updated to take account of changes and updates to the plant configuration.

Process plant engineers work with traditional 2D plant drawings, such as Piping and Instrumentation Diagrams (P&IDs), Process Flow Diagrams (PFDs) and hook-up drawings and these will continue to be essential for plant operations and maintenance.

For this reason, our partners at Geologix, have built a seamless link between the 2D drawings and their equivalent Digital Twins, enabling users to work in both environments in true synchronisation.

Figure 2 below, shows a discharge cooler, on the same gas processing facility, with a direct link between the PFD and the Digital Twin. This provides a very valuable method of identifying where equipment items are located on the plant, something that is not obvious to anyone supporting the plant remotely.

For some years, Geologix has been involved in the design and installation of Collaborative Work Environments (CWEs) for both oil and gas drilling and production. These are work rooms where experts from operator and service companies can share knowledge and make informed operational decisions, as well as addressing problems as they occur.

Some operators have invested very large amounts of money in these environments but physical CWEs come with a number of problems in addition to cost – they cannot be re-configured easily as operational requirements change, personnel must be in the CWE to contribute and the rooms occupy building space whether in use or not. Through experience with Virtual Reality, our partners are now able to offer a virtual CWE (vCWE) which solves these problems and is much lower cost to set up.

Figure 3 below, shows a core sample and subsurface information in a vCWE during a drilling operation.

The virtual CWE mimics a physical CWE by having large display panels on the walls showing live operational information. In the physical room, experts collaborate around the display panels and generally, there is a video conference link to the control room in the plant or offshore platform/refinery.

As the control room operators are remote from the CWE, it is difficult for them to share in the same collaborative experience. With the virtual model, personnel can collaborate remotely. They can join the room from anywhere with a good internet connection.

Figure 4 below, shows three work panels that are available to everyone in a virtual CWE meeting. Participants can walk around the virtual room and interact with the work panels as in a physical room. They have voice communications either by conference phone or VOIP (voice overIP). It is very easy and quick to set up multiple vCWEs as required, which makes them ideal for adapting to changing operational requirements.

Future Energy Partners can bring multi-disciplinary teams to tackle Remote Operations projects, underpinned and enabled by Geologix software and expertise. The social element of remote working and making the change from business as usual to this way of working will be the subject of a future article. Needless to say, people and their capability are critical to the success of these new ways of working.

We are grateful to Future Energy Partner for helping us though the ISO certification process. The implementation of ISO standards is what differentiates as a company from our competitors and demonstrates our commitment to Occupational Health and Safety Management.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.